I know, I know. I have neglected this blog entirely for the last 4 months. In my defense, a LOT has been going on: David started a job, I started a job, we moved, I went to the LMDA Conference, worked on 2 summer festivals, attended numerous plays, became a responder for Theatre Roundtable, taught classes for Columbus Children’s Theatre, went to the Shaw Festival, AND… the reason I post today… I’ve been pouring myself into a production of Shakespeare’s TITUS ANDRONICUS. After months of work on the script (I did an adaptation of it for the production) the show is finally ready to open on Thursday, September 8. Shepherd Production’s presents TITUS ANDRONICUS at MadLab Theatre & Gallery, 227 North 3rd Street, Columbus, OH 43215. Parking is free in the large lot beside the building. Tickets are only $15, $10 for students and seniors. Shows are September 8, 9, 10, 15, 16, and 17 at 8pm and 11 at 2pm. Buy tickets online at http://www.madlab.net.

Here’s a special sneak preview for you: a look at the dramaturgical note I wrote for the playbill:

“REVENGE, WHICH MAKES THE FOUL OFFENDER QUAKE”: A CLOSER LOOK AT WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S TITUS ANDRONICUS

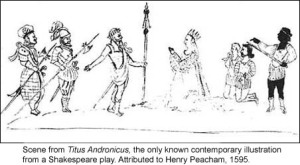

“VENGEANCE IS IN MY HEART, DEATH IN MY HAND, BLOOD AND REVENGE ARE HAMMERING IN MY HEAD,” exclaims Aaron the Moor, a sentiment shared among nearly every character in William Shakespeare’s Roman tragedy, TITUS ANDRONICUS. To many who know it, TITUS may seem almost impossible to produce: the script calls for nearly 30 actors, 6 on-stage murders (not to mention the many others we do not get to see), and countless acts of unimaginable violence. One of Shakespeare’s earliest works, its excess of blood-thirsty revenge fits into the “Revenge Tragedy” form, a theatrical genre that was wildly popular in Elizabethan England. In the early 1590s, revenge plays like Thomas Kyd’s THE SPANISH TRAGEDY and Christopher Marlowe’s THE JEW OF MALTA were as popular as action and horror films are today. In writing TITUS, Shakespeare joined their ranks and achieved his first commercial success. TITUS ANDRONICUS, however, takes revenge beyond graphically violent entertainment, to a place where racial prejudice, war, violence against women, and the human capacity for brutality are often more shocking than the blood and gore.

Titus Andronicus is a highly respected Roman Army General, having led his nation to victory against the Goths on numerous occasions over the course of his illustrious career. His latest triumph comes complete with spoils of war: Tamora, the Queen of the Goths, her three sons, and her wicked servant, Aaron the Moor. Titus returns only to discover that Rome’s emperor has died, and while the people would prefer the great Andronicus to be their leader, Titus graciously defers to the emperor’s eldest son, Saturninus, who in turn chooses Tamora to be his bride. The insertion of the Gothic leaders into the royal ranks of Rome provides the necessary accessibility to those upon whom the captured Goths aim to exact revenge. When Tamora’s sons rape and mutilate Titus’ only daughter, Lavinia, at their mother’s behest, the endless cycle of manipulation and destruction between the two families is set in motion, each atrocity exceeding the last.

career. His latest triumph comes complete with spoils of war: Tamora, the Queen of the Goths, her three sons, and her wicked servant, Aaron the Moor. Titus returns only to discover that Rome’s emperor has died, and while the people would prefer the great Andronicus to be their leader, Titus graciously defers to the emperor’s eldest son, Saturninus, who in turn chooses Tamora to be his bride. The insertion of the Gothic leaders into the royal ranks of Rome provides the necessary accessibility to those upon whom the captured Goths aim to exact revenge. When Tamora’s sons rape and mutilate Titus’ only daughter, Lavinia, at their mother’s behest, the endless cycle of manipulation and destruction between the two families is set in motion, each atrocity exceeding the last.

TITUS ANDRONICUS is thought by many to be set in the 3rd century AD, a period in Roman history referred to as the “Crisis of the Third Century” due to the many emperors who claimed the throne over a relatively brief period of time. The look of our production, most notably the weapons and costumes, takes inspiration from this period. While the characters are entirely fictional, many of them are inspired by historical figures in some way or another. The historical inaccuracies, however, are far more frequent than the facts. Like many of Shakespeare’s plays, the foreign setting is often recognizably English in nature, but incorporates some of Shakespeare’s knowledge of Rome and the classics. He utilizes Latin and also incorporates what he would have learned about the Roman government and their military from classical texts like Plutarch’s Lives of the Roman Emperors. Events surrounding the rape of Lavinia are very similar to Ovid’s “The Tale of Philomela” from his Metamorphoses. In the story, Philomela’s brother-in-law Tereus locks her in a cabin and rapes her, cutting out her tongue so she’ll be unable to tell who committed the crime. She instead sews his name to confess to her sister, Procne, who then kills the children born by Tereus and feeds them to him baked in a pie (see how Shakespeare one-ups this horrific story in TITUS). Despite the bits of the play borrowed from history and from myth, it is more important to recognize this as a time when a major empire was on the verge of collapse, where years of war had weakened Roman society and soon it would cease to exist. Shakespeare’s audience would have recognized this as the end of an era, and that all of this death and destruction is occurring in vain because soon there will be no Rome for which to fight.

To say this play has a bad reputation would be an understatement. To this day, TITUS is rarely performed because many believe the writing to be poor in comparison to Shakespeare’s later works. The physical violence can be so over-the-top that directors tend to shy away from the play for fear the brutality will surpass the frightening into the comical. Not to mention the treatment of Lavinia and the behavior of Aaron, which are quite difficult to stomach for a modern audience. Lavinia is used and abused both physically and metaphorically; she is considered a form of currency by her father and every other man she meets, being passed around from man to man until any agency she has left is quite literally ripped from her body. Aaron, on the other hand, is perhaps the most powerful character in the play, manipulating his surroundings to his liking and feeling no remorse for it. His speeches are some of the most eloquent in the play and the role is considered one of the most finely penned and most challenging villains in all of Shakespeare. None of this, however, changes the fact that this methodically evil character is black, and his faults are blamed on such by the fairer skinned characters in this world. Without careful staging, Shakespeare’s treatment of this character could simply be viewed as racist, unless the production can separate the racism of the characters from the perceived racism of their creator.

So with all its challenges, not only why, but how does one put on this play in 2011? To address the latter, we’ve adapted the original script to feature only 16 actors. Contradictions and confusions have hopefully been eliminated through the conflation or removal of extraneous characters and the cutting of repetitive lines and scenes. The production aims to emphasize the underlying manipulation and verbal aggression in the text, taking focus away from the excessive physical violence and putting it instead on Shakespeare’s prowess with words. As for the “why,” what could be more relevant today than witnessing a society entangled in an ongoing war rooted in revenge? It seems fitting that this play will be performed on the 10th anniversary of September 11, a reminder of the death, destruction, and debilitation the last 10 years have brought on our society as the result of the response to our own “rape.” In TITUS ANDRONICUS, Shakespeare dares to show us the horrific lengths to which a General, a leader, a father, and a human being will go to avenge wrongs against him, and the consequence is the perpetuation of violence across generations to come.

KATE TULL

Dramaturg

Awesome! I can’t wait to come see the show!